- Home

- Today’s Morocco

Today’s Morocco

The Arabic term for Morocco, Al Maghrib, etymologically means "the place where the sun sets", "the west". To this oriental Finistère, the ancient Arab geographers gave the name of "The Furthest West". Therefore, it’s the western part of the Orient and still a little mysterious in the eyes of the European traveller. A Morocco that we therefore expect to find something familiar in.

However, as soon as we set foot there, the feeling of being truly somewhere else takes over. This strangeness is also part of the root of the word Al Maghrib, which evokes at the same time as the setting sun, distant travel and exile. Today’s Morocco exists at a time of globalisation and technological progress, while retaining its own political, social and cultural heritage. In this, it continues to adhere to the meaning that its Arabic name carries: close and foreign at the same time. Like a coin, it has two sides.

Urban and rural world

Morocco currently has more than 36 million inhabitants, whereas there were only 11.6 million in 1960. Mostly rural until 1988, 55% of Moroccans are today city dwellers, although the rural exodus is still relatively restricted. But the precariousness of life in the countryside leads small peasants to give in, more and more, to the call of the city in the hope of finding a job and better living conditions there.

What is striking is rapid population growth and a trend towards concentration in the cities as well as the gap that separates the urban world from the rural world. The tourist slogan “Morocco, land of contrasts” undoubtedly applies to the beauty of the landscapes, the diversity of the population and the cultural richness of the country. It is also relevant for expressing, in a concise manner, the regional, social and economic inequalities that characterise it.

The medina, open to the world yet secret

The medina, which constitutes the core of the city, retains its traditional layout and architecture. It remains the favoured place of the small souk and “kissaria”, corporations of traders and craftsmen; its living quarters are arranged around four essential points, namely the mosque, the fountain, the hammam and the oven.

However, while tradition remains alive, this does not exclude the penetration of certain forms of modernity into everyday life. Whether we celebrate it or deplore it, the medina of today sees the very cheerful co-existence of age-old pottery with plastic; of djellaba alongside copies of what is fashionable in West; the chanting of the Koran mixed with the latest successes of rai, rock or techno music; minarets decorated with copper balls and rooftops bristling with satellite dishes.

A very open place, therefore, despite the walls that surround it and separate it from the modern city. This opening up to the world of the public sphere does not in any way alter private space. Whether they are modest dwellings or rich palaces, the privacy of families is preserved from the outside gaze by blind facades and door openings in the shape of a chicane. Abandoned by the big-city families, who prefer huge, sometimes flashy villas in the upscale districts of the modern city, the beautiful old residences of the medina are either occupied or used by families from a working-class background and who are often from the countryside, living en masse, and without the means to maintain them.

The Moroccan city: Two within one

A country of strong rural traditions, Morocco has also developed a remarkable urban civilisation. Its imperial cities, Rabat, Fez, Meknes and Marrakech, bear witness to the influence that they have had since the Middle Ages. Today, the large Moroccan cities have two aspects: the traditional city, or medina, and the modern city, born with French colonisation and often called "the new city".

The Moroccan countryside: The iron pot and the earthenware pot

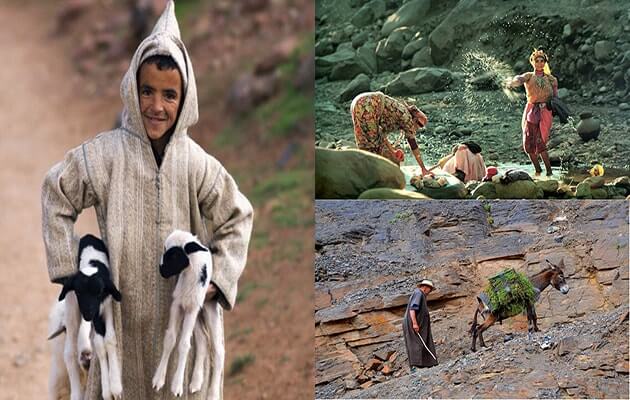

It is in the rural world that the profound transformations that have taken place since the beginning of the 20th century are the least visible to the passing visitor.

Very often, the latter will only remember the image of a local peasant turning over a piece of land with an antique plough, yet also happens to see vast fields worked with the help of modern machines. What is the truth of the matter? The Moroccan countryside, which is largely dependent on physical and above all climatic constraints, is also the product of the history that shaped them. Its traditional organisation, around the tribe, based on the pairing of culture and livestock, was upset by colonisation, which seized most of the best land, and called into question the methods of usage and occupation of it. As a result, two types of farms have emerged: small properties alongside large estates practising intensive cultivation.

This configuration persisted after independence. Colonial land, which was nationalised in stages in 1959, 1963 and 1973, passed into the hands of the state and large landowners or was distributed to small landless peasants who were invited to join co-operatives. This redistribution was accompanied by a program to modernise land by consolidation, irrigation and electrification in order to reduce social inequalities and contain the rural exodus. Today, however, out of 1.5 million farms, 70% have less than a hectare and represent around 2 million hectares of usable agricultural area out of a total of almost 9 million. The remaining 30% occupy three-quarters of the country's agricultural land.

In this very marked duality, the share between the iron pot and the earthenware pot is all the more unequal as the whims of the weather get involved.

The modern city: courtyard and garden

The modern city was designed by Resident General Lyautey, with the help of prominent urban planners, such as Prost and, later, Ecochard, as a separate entity from the medina. It housed, at the outset, the administration and infrastructure services set up by the French protectorate. The European population built its neighbourhoods there, with shops, cafes, restaurants and cinemas. If today this part continues to be designated as the city centre, it has nevertheless lost its prestige. Deserted by the middle class, it is above all a place of daytime activities: a universe of minor civil servants and, more generally, employees of the tertiary sector. We work there during the day and stroll around at nightfall, after the coffee and cream-pastry ritual, enjoy ourselves from 6 to 8 pm in the many "tea rooms".

Little by little, the modern city has grown. The former patrician families who were at the origin of the peripheral residential districts - where the rare businesses are supermarkets - are today joined by the nouveaux riches, emerging from the mediums of business and upper echelons of the civil service. Here, the days are spent, sheltered by high walls, in often rowdy luxury, among lush vegetation. On the other side, in a sort of distant mirror image, well representative of two-speed Morocco, are the working-class districts. Close to the shantytowns that disappeared here to recreate themselves over there, they sometimes take on the appearance of dormitory-towns built in the 1970s without any overarching aesthetic concern and without major urban necessities, sometimes in the form of fairly anarchic housing estates planted with small buildings which, dependant on the family budget, remain unfinished for a long time.

Water, the precious resource

For years, Morocco has suffered from severe periods of drought which make the rural world highly dependent on the country's water resources. The centuries-old irrigation techniques, still in use today, testify to the know-how and ingenuity of the Moroccan population to capture water. Diversion dams, seguias, khettara, wells and norias have long been built in mountains and oases. From the early 1960s, a policy of large dams (previously implemented by the French protectorate) was accelerated by independent Morocco, for irrigation, hydroelectric production and the supply of hydroelectric-produced drinking water and reservoir drinking water. Apart from these large spaces, small irrigated areas were created thanks to the development of motor pumps. Often introduced by Moroccans resident abroad (settled in France, Belgium, Holland, Italy) who devote part of their income to improving the living and working conditions of their loved ones who stayed in the village and who initiate development projects, these motor pumps replace traditional processes. This is now the case in oases.

In order to combat the deterioration of the economic and social situation in rural areas, due in large part to drought, an inter-ministerial program adopted in 1999 provides for hydraulic installations, drinking water supply, electrification, road construction, development and maintenance of rural schools plus cancellation and deferral of debts for small farmers. These are all measures to respond to the emergency, to try to reduce the gap that separates the rural world from the urban world and stem the exodus towards the cities.

To the magnitude of these problems is added a paradox: the big landowners (ruling family, those with power bases, high officials and high ranks in the army, patrons or shareholders and officers of the army, bosses or shareholders of companies as well as holdings) not living in the countryside, hardly perceive the interest that there is in the long term - for all, including them - to stabilise the rural population through the help which they could provide to bring in equipment and in social and cultural support.

Small farmers are today marginalised in the face of agrarian capitalism, which has been the main beneficiary of previous policies (major irrigation works, tax exemption granted to the agricultural world from 1984 to 2000) and which will be best equipped to support, from 2010, the effects of the free trade agreement signed in 1995 between Morocco and the European Union.

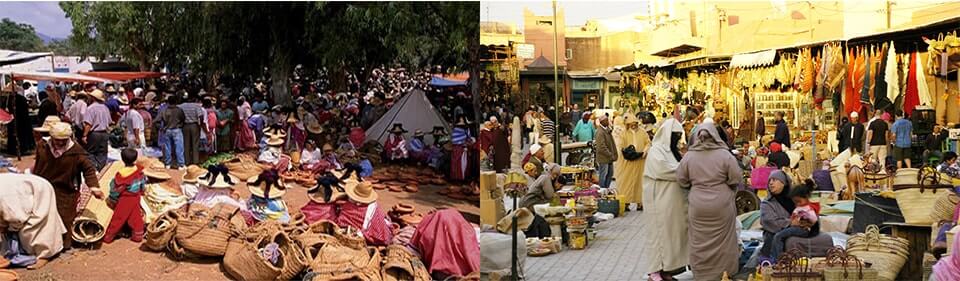

The souks: a city-country relationship

A veritable town of tents, erected for a few hours on a clay surface, the souk is organized into "streets" and "districts" where shops and trades are grouped by speciality. Often leaving their villages at dawn, the peasants arrive at the souk in cohorts, after having travelled long distances (10 km and sometimes more) on foot, on the back of a donkey or mule, by bus and, more recently, in the back of small vans of Japanese brands. They bring their agricultural and craft products there: grains, fruit, vegetables, cattle, poultry, but also pottery, wool and carpets. They leave with products from the city: sugar, tea, spices, butane gas, plastic utensils. Artisans, meanwhile, offer traditional services (sewing, shoemaking, blacksmithing, hairdressing and traditional medicine) and more recent services: repair of radio cassettes, televisions and mopeds.

The souk is also a place of contact with the administration. Various matters are settled there: civil status, justice, mail and visiting the dispensary; some medical and social information is received there (vaccination, malnutrition, family planning and contraception, etc.). But in the pull of two siren voices, which of the two will be heard the most? That of the official of the ministry of health presenting the respective qualities of the IUD and the condom? Or that of the huckster selling the miraculous effects of his preparations on sexual impotence?

Finally, the souk is a space of conviviality. In the tent, the meals of your choice, of tea, skewers, kefta (minced and grilled meatballs), tajines and doughnuts allow you to eat, relax and converse in company before taking the long road back. More and more, the souk gives birth to a new city, thus contributing to the urbanisation of the countryside. This is the case when it is located near a highway, or when fixed businesses are established in or near its perimeter. A small town with the appearance of a relay or road stopover then develops along the axis of communication, sometimes until it moves the souk from its original space and pushes it out of the centre